By Grace Segran

SMU Office of Research and Tech Transfer – Pricing climate risks properly today reduces the possibility of wealth transfers between uninformed and sophisticated agents, and the likelihood of extreme price movements in the future. As shorelines shift and extreme weather hits more frequently, regulators are concerned that markets do not have sufficient experience in dealing with such risks and may not be paying enough attention to them.

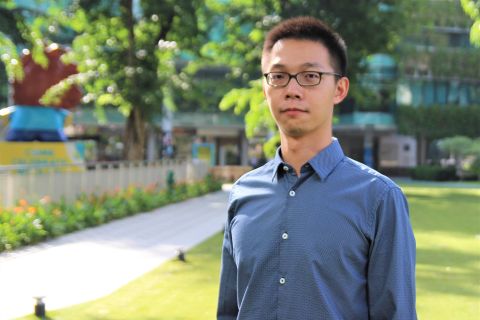

To address this important issue, SMU Assistant Professor of Finance Li Weikai, and his fellow researchers, studied the efficiency with which the stock prices of food companies respond to trends in droughts across the world. The Finance Professor’s research areas include Asset Pricing and Capital Markets; Sustainable Finance; and Financial Market Soundness, Change, Risk and Resiliency.

The basis for Professor Li’s study, published in the research paper ‘Climate risks and market efficiency,’ was that among the natural disasters that might be amplified by climate change such as drought, heat waves, floods, and cold spells, drought is considered one of the most devastating for food production. The food industry in countries suffering adverse trends in droughts are likely to experience lower profits since this industry is reliant on water and hence sensitive to drought risk.

Using data from thirty-one countries with publicly traded food companies, the researchers ranked the countries each year based on their long-term trends towards drought using the Palmer Drought Severity Index.

“The models predict future precipitation patterns and the risk of drought with some degree of accuracy,” Professor Li says.

The researchers found that poor trend rankings forecast poor subsequent growth in profitability of the food industry in a geographical location. Says Professor Li: “This excess return predictability is consistent with food stock prices underreacting to climate risks. Our research confirms regulatory worries about markets underreacting to climate risks.”

According to Professor Li, one reason the market is underreacting to climate change risk is that investors do not know a firm’s exposure to the risk since firms are not required to report it in their financial statement or annual report. “One way for governments to solve or alleviate this issue is to promote mandatory disclosure of a firm’s exposure to climate risk.”

Pricing climate change risk

So how is climate change risk priced and how is this reflected in the stock market context?

“(In the context of our research), food companies rely heavily on water or other exogenous environmental variable. Using historical data, fund managers and investors can look at the relationship between past weather conditions and how they relate to the company's bottom line, and then see whether there is a significant statistical relation,” Professor Li tells the Office of Research and Tech Transfer.

Based on this historical estimation, the managers and investors extrapolate into the future by using a projection from the climate models and see how the company's profits might be negatively impacted in the future when the global mean temperature rises further. With that information, they can properly discount the price of the companies that are most vulnerable.

Professor Li notes that it is more difficult for individual companies to come up with a specific value as they have few data points. Therefore, they rely on the entire industry or a larger sample to estimate the relationship between the weather and the firm’s profits. A standard valuation model like the discount cashflow model can then be used to reevaluate the firm’s stock market value. “Once you’ve priced the risk and you believe a firm is more likely to be vulnerable to climate change and the firm’s stock price is not fully reflecting this increased risk, then you should probably sell and/or adjust the weight in your portfolio.”

These measures can be easily used by managers and investors, says Professor Li. However, the question is whether they have the knowledge to understand how the climate risk impacts their bottom line. “That’s the main factor that could impede their ability to price in, or take adaptive actions towards, the climate change risk.”

Mortgage lending

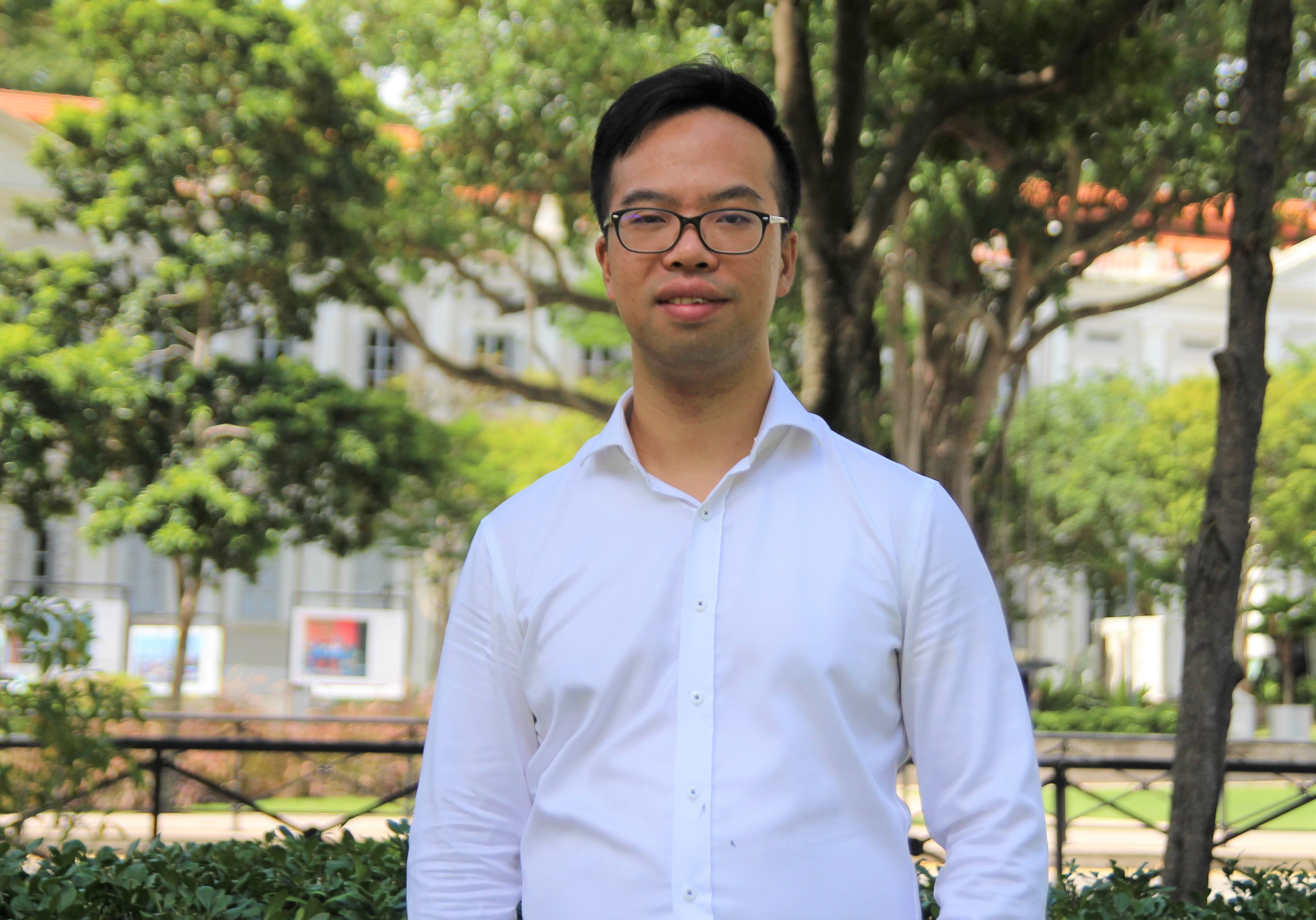

In Professor Li’s working paper titled ‘Climate change and mortgage lending,’ he and his fellow researchers examine whether mortgage lenders account for climate change risk when originating mortgages.

“We examine whether agents’ beliefs and concerns about climate change affect their real decision-making and adaptive actions. We found that the loan officer’s lending decision depends on how they perceive or what they believe about climate change,” he says. “If the loan officer is a strong believer of the climate change risk, the officer is more likely to reduce lending in areas that are most vulnerable to climate change.”

In order to find a measure that can correlate or reflect a local lender’s belief in climate change, the researchers used local temperature variation. The logic is that people perceive greater climate change risk or global warming based on their own experience. “This is very intuitive; it may or may not be rational,” he argues. “However, it is supported by psychologists’ studies that people's decisions are more likely to be influenced by their personal experience rather than some abstract statistical data.”

The study found a strong negative effect of abnormally high local temperature on mortgage lending at the U.S county level. The economic effect is significant: a 1°F increase in the past 36-month average temperature anomaly in a county reduces the mortgage approval rate by 0.8 percentage points and the loan amount by 6.5 percent in an average county. “This effect does not seem to be driven by changing local economic conditions and demand for mortgage credit. It is considerably stronger among counties with strong beliefs in climate change and counties most exposed to the risk of an increase in the sea level,” he concludes.

Back to Research@SMU Feb 2020 Issue

See More News

Want to see more of SMU Research?

Sign up for Research@SMU e-newslettter to know more about our research and research-related events!

If you would like to remove yourself from all our mailing list, please visit https://eservices.smu.edu.sg/internet/DNC/Default.aspx