By Vince Chong

SMU Office of Research – A decade ago, a Singapore Management University academic took in the sights of colourful, healthy corals playing host and habitat to myriad marine creatures at the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.

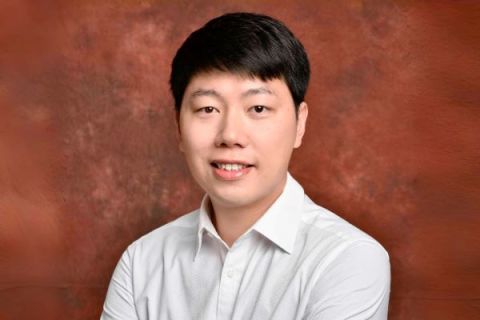

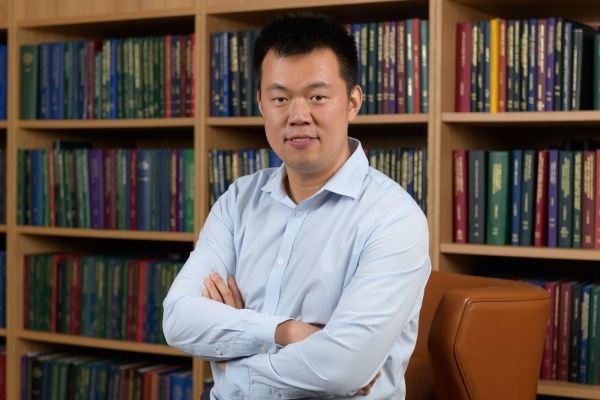

It was not an entirely enjoyable episode however, given that Associate Professor of Law Liu Nengye had to navigate bleached and dead corals to get to the surviving ones. A more recent trip to Mersing, Johor, along the east coast of Malaysia, confirmed growing fears of marine degradation: he found not a single coral spot there.

Such experiences reaffirm his longstanding research work into global marine conservation laws and policy, and he acknowledges that it is an uphill task.

“I was very surprised [at Mersing]. Coral reefs are very sensitive and their wellbeing is a good indicator of the health of the marine environment in general,” Professor Liu tells the Office of Research.

“[Corals] are habitats, a foundation, for other marine species and require a delicate balancing in ocean temperatures and salinity to thrive. What has happened shows the kind of trouble our oceans are in.”

His ultimate aim, he adds, is the return of the oceans to a “peaceful and sustainable” state.

Among his recent work is a research paper Beyond UNCLOS – Marine Environmental Protection in a Changing World, which introduces developments in UNCLOS – the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It argues that the 40-year-old treaty alone is “insufficient to cope with the interconnected global challenges of today’s world for thriving marine futures.”

Coauthored with another SMU academic, Associate Professor of Law Michelle Lim, the paper also assesses the ability of UNCLOS to effectively tackle marine biodiversity challenges under conditions of global change. It notes, among other things, “a great opportunity” for a recent global treaty, the Agreement for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ), to fill a regulatory gap in conservation of the high seas. However, its remit across only four thematic areas might not be wide enough.

Nevertheless, the paper concluded that in today’s world “where people and countries are inevitably connected through migration, trade, tourism and technology, the UNCLOS, though not capable of solving massive marine biodiversity loss alone, can still play a significant role in addressing the problem.”

Not all bad news

Nearly two decades ago when he embarked on his academic journey, Professor Liu focused his research on marine pollution from shipping and how it was legally enforced by countries. In recent years, he studies marine biodiversity regulations, specifically around the fisheries sector where overfishing or industrialised fishing have caused unsustainable loss of fish stocks and other marine species. These research areas, he says, form two of three interrelated components when it comes to the conservation of global oceans, the other being climate change, or global warming.

What it also means is that the academic – who has addressed the European parliament at the 2021 World Ocean Day, and spent time at the Arctic studying and observing sea life migrating to cooler waters in the face of rising ocean temperatures – is well placed to assess what works and what doesn’t when it comes to laws that govern the health of our high seas.

Take marine pollution for example, he says. As a result of global standards set up by treaties between countries and international bodies, port authorities and relevant bodies have vigorously enforced rules to ensure ships plying the seas do not pollute excessively.

These standards include, for example, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78) and the 2004 International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships' Ballast Water and Sediments. They have, among other things, improved management of waste and garbage onboard marine vessels so that less of the stuff spoil the ocean.

“So the curbing of pollution in the water is a success story,” Professor Liu says.

“It is proof that we can make things better.”

There is hope as well in the fisheries area, he adds, even in the face of depleting stocks of fish and other marine life over the years. This comes partly on the back of growing demand for seafood among modern societies due to its relatively healthier nutritional profile.

“That said, using global standards and laws to better manage fishing industries and change mindsets, the population of certain whales, for example, are gradually recovering,” Professor Liu notes.

“We are going in the right direction but of course, much more needs to be done.”

“Genuine intentions… but different considerations get in the way.”

What doesn’t help, he says, are issues like rising global consumption and geopolitics. The first factor has manifested itself in bigger ships that produce more carbon emissions simply due to their scale, and adding to ever-rising greenhouse gases. This ties into global warming, the third component for marine conservation.

With 80-90 percent of all goods carried by sea, some estimates put deadweight tonnage of container ships at nearly 300 million metric tons in 2022, up from 11 million metric tons in 1980. In that time, the weight of cargo shipped globally has risen to 1.95 billion metric tons from 0.1 billion metric tons.

Other vessels such as cruise ships have also grown, doubling in size over the past 20 years and producing 20 percent more carbon emissions in 2022 than in 2019, before COVID.

“They used to call them large container ships, now they’re called super large… bigger and bigger but with similar energy efficiencies,” Professor Liu notes.

These are issues that UNCLOS can help address. As Beyond UNCLOS notes, the treaty “may utilise ‘rules of reference’ to work with UN Specialized Agencies on specific issues.”

Back to Research@SMU November 2024 Issue

See More News

Want to see more of SMU Research?

Sign up for Research@SMU e-newslettter to know more about our research and research-related events!

If you would like to remove yourself from all our mailing list, please visit https://eservices.smu.edu.sg/internet/DNC/Default.aspx