By Jeremy Chan

SMU Office of Research & Tech Transfer – As civilisations arose over the span of human history, people began to organise themselves into groups that abided by certain sets of rules. Typically, these rules serve to protect fundamental rights and define acceptable behaviour in society. Some rules are fiercely guarded and have remained unchanged over time, while others have either been discarded or updated to reflect changing realities.

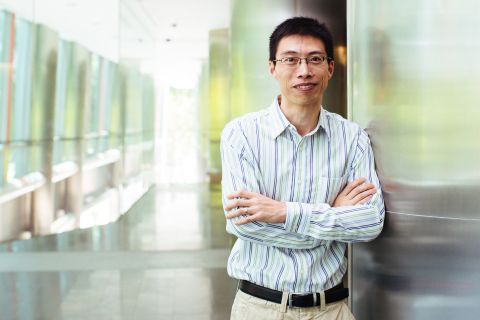

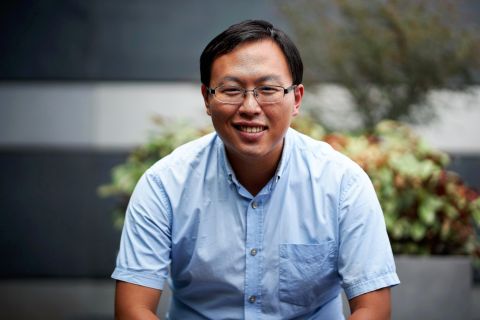

In a democracy, legislation and constitutions are crafted through iterative dialogue between citizens and the politicians who represent them. The outcomes of their discourse can have path-dependent and far-reaching consequences, says Professor Elvin Lim, a political scientist at the Singapore Management University (SMU) School of Social Sciences. Professor Lim, who is also Dean of the Core Curriculum at SMU and Director of SMU’s Wee Kim Wee Centre, seeks to unravel the legacy of seemingly simple decisions made hundreds of years ago concerning issues such as presidential elections or the wording of constitutional clauses.

“My research aims to understand collective human behaviour, in particular, how specific rules and institutions structure our behaviour to generate both intended and unintended outcomes,” he says.

Rhetoric, the media and public opinion

An interest in political rhetoric in the US drew Professor Lim to his field of study. “Politicians and aspiring politicians in the US do not speak like their counterparts from parliamentary systems,” he notes, drawing on observations from his research in 2002, where he analysed 264 inaugural addresses and annual messages delivered by US presidents between 1789 and 2000.

“Presidents, in general, are more likely than prime ministers to deploy rhetoric that would appeal to regular citizens,” he says. These differences in word choice and style of delivery arise from the way presidents and prime ministers are elected, he adds – a president is voted into power directly by the people, whereas a prime minister is appointed by elected members of the ruling party. “Hence, prime ministers have to not only convince the public, but also their backbenchers in parliament who may not be as easily persuaded by emotional or human-interest appeals as an average citizen.”

Given the power of political rhetoric to sway public opinion, the media is an important player in politics, amplifying the reach of politicians while simultaneously providing a channel for criticism of political figures. In a book chapter published in The Presidency and the Political System, Professor Lim examined the relationship between the US presidency and the media, highlighting the challenges of modern dynamics such as the blurring of lines between news reporting and entertainment, campaigning for office and governing.

“Political communication is becoming more and more like corporate and personal communication – the boundaries between previously discrete spheres in life are dissipating in an era of mass communication,” he explains. “And so, as media conglomerates restructure and rethink how news and entertainment are packaged, the world of politics must also brace for a time of disruption. Old parties, norms, and codes of conduct must give way, for better and worse, to new modes of interaction with the electorate, and, possibly, new ruling elites who understand these new techniques of persuasion.”

Lessons from history

Professor Lim’s more recent work focuses on political foundings, tracing the origins of constitutions and their downstream implications. In a 2018 paper in the UCLA Law Review, Professor Lim noted that the US was founded twice, not once – the first founding established state governments and the second, the federal or national government.

Because the rules established during the second founding did not completely overwrite those of the first founding, the US Constitution in its current form sometimes struggles to balance the distribution of power and rights between state governments and the federal government. This is a classic example of how political settlements negotiated in the past continue to have repercussions in the present and the future, says Professor Lim.

Although Professor Lim’s research revolves around US politics, he believes that there are interesting lessons to be learnt from comparing political systems and outcomes, some of which are applicable to new and developing states in Asia or other parts of the world. For instance, he emphasises the importance of striking a balance between continuity and adaptability when constructing rules for a polity.

“Constitutions that can be overthrown or overwritten easily with simple legislative majorities usually aren’t worth the paper on which they are printed. Conversely, constitutions that are too rigid and offer few provisions for amendment and evolution are more dangerous than helpful, because in some polities, the only way out is revolution,” he cautions.

Changing doctrines

In ongoing work, Professor Lim is investigating how bodies of thought, such as those in politics and religion, interact with one another to produce “synthesised, hybrid doctrines that are more than the sum of their parts”.

Consider globalisation, a phenomenon with an accompanying set of legitimating ideas that was once confidently promulgated with relatively little attention to its potential limits and its detractors. The glamour of globalisation has since waned, and has generated “a dissenting vector of discontent in every society of our global community”, says Professor Lim. He points to Brexit and the election of US president Donald Trump as two events that have triggered a reconsideration and a reinterpretation of the promises of globalisation, possibly towards a new synthesis such as in what some observers have called ‘glocalisation’.

Newton’s third law states that “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction”. This seems just as true for politics as it is for physics. “Very few movements in our world are unidirectional, because it is in the nature of complex humans to react. So, in peculiar but predictable ways, wealth can generate poverty; globalisation can trigger protectionism. In a more interconnected world, we will do well to appreciate that ‘progress’ itself galvanises conservative reaction,” says Professor Lim.

But this offers challenges as well as opportunities – humans do need to be disabused of our natural confirmation bias; we do need reminding that reasonable people can and do disagree with us, adds Professor Lim. “Thus, the art of politics and government is to painstakingly, in the face of opposing viewpoints and commitments, bring dissenting parties to the negotiation table to fashion for each generation an evolving governing consensus,” he says.

Back to Research@SMU Issue 59

See More News

Want to see more of SMU Research?

Sign up for Research@SMU e-newslettter to know more about our research and research-related events!

If you would like to remove yourself from all our mailing list, please visit https://eservices.smu.edu.sg/internet/DNC/Default.aspx