By Michelle Lee Twan Gee

SMU Office of Research & Tech Transfer – What might we learn from quantitatively studying Singapore’s Court of Appeal judgements using network analysis? The answer, discovered SMU Assistant Professor of Law Jerrold Soh, who is also the Chief Data Scientist of legal tech startup Lex Quanta, is fascinating.

Network analysis is a set of techniques for analysing relations among items, taking into consideration how a set of items are connected to one another.

In a paper published last year in the Singapore Academy of Law Journal, Professor Soh, who specialises in Empirical Legal Studies,Law and Economics,and Law and Technology,detailed what he found from a network analysis of virtually all reported Court of Appeal judgments handed down from 2000 to 2017.

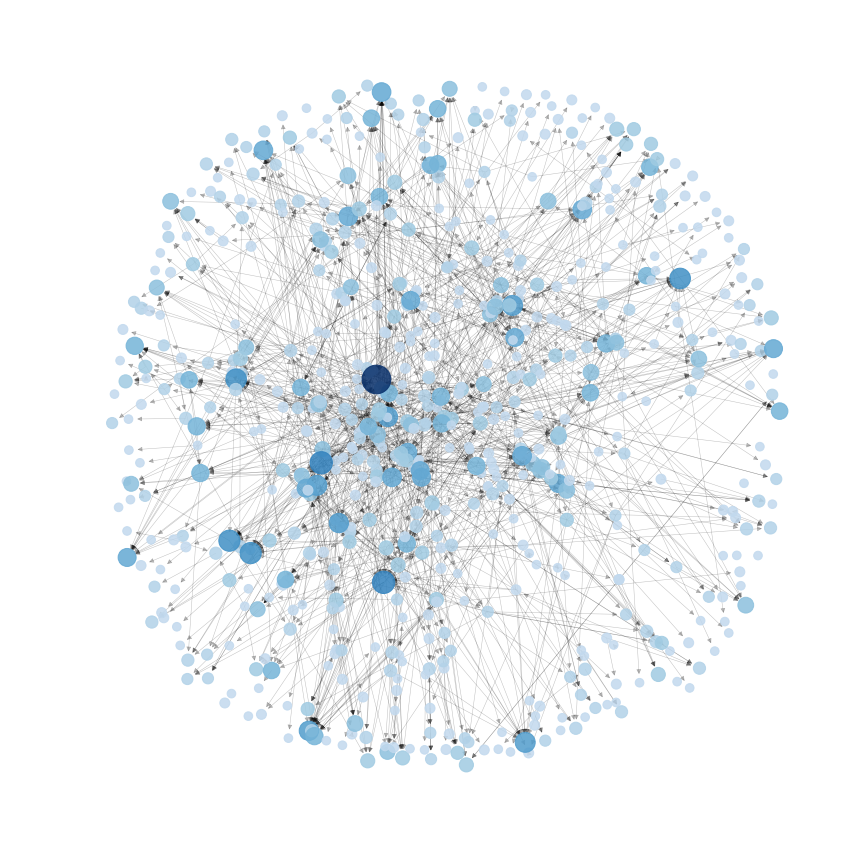

As Singapore’s legal system is based on the English common law system, judgements written for one case would typically cite previous judgements written in earlier cases. This entire body of citations can be rendered as a network (Figure 1), with each case represented as a ‘dot’ and citations as ‘lines’ between these dots.

Figure 1: Network of citations, where each ‘dot’ represents a case and the ‘lines’ represent citations

“In this system of dots and lines, a dot that has a lot of lines connected to it basically has been cited very often by subsequent judgements,” Professor Soh explains. “By measuring what we call the degree, or the number of lines attached to each case, you can start to see how important, or ‘central’ a case is to the legal network.”

“A simple measure of centrality is just looking at the in-degree, which is the number of incoming lines (i.e. citations received). You can also look at the out-degree which is the number of other cases which a particular case refers to. A case that refers to a lot of other cases might also be quite important to look at.”

Building on that intuition, a more sophisticated way to measure centrality – or how important an item is in a network based on the density of its linkages to other items – is to simultaneously calculate two scores for each item: a hub score, and an authority score. These measures go beyond looking merely at the quantityof citations received or given, and try to account for the qualityof each citation.

This is by continuously factoring in the degree of the othercases that link to a particular case. A strong hub is a dot that points to many strong authorities, while a strong authority is a dot linked to by many strong hubs. This may sound circular, but there is a way to calculate these scores using a well-established algorithm.

Rich insights into Singapore’s legal system

The analysis offered up rich insights into Singapore’s Court of Appeal judgments.

The first finding was the growing sophistication and complexity of Singapore jurisprudence. This is physically manifested in a complex and highly-connected network diagram which Professor Soh presents in the paper. “We have a nucleus of interconnected cases that cite and are cited by each other, which is supported by an orbital of peripheral jurisprudence.”

Another fascinating finding was that all five judgments which came up as the most central by authority scores deal specifically with issues concerning either the interpretation or implication of contractual terms. These cases are Zurich Insurance (Singapore) v B-Gold Interior Design & Construction, Sembcorp Marine Ltd v PPL Holdings, Panwah Steel v Koh Brothers, Sandar Aung v Parkway Hospitals Singapore, and Man Financial v Wong Bark Chuan David.

These algorithmically-produced results, noted Professor Soh, were consistent with legal domain knowledge. The case of Zurich Insuranceis a widely-known landmark case laying out the contextual approach to contractual interpretation in Singapore. The second case, Sembcorp Marine,reinforces the contextual approach and is itself a leading case on terms implied in fact. These results, in turn, revealed that interpreting contracts and determining when, and what happens when, terms are breached is a highly central (and often litigated) aspect of Singapore law which legal educators could focus more on.

Yet another interesting discovery is that the influence of Singapore contract law, particularly the rules on contractual interpretation, has stretched beyond contract law alone. Although Zurich Insurancehad been cited by 31 subsequent cases, nine of those were not contract law cases per se.

Across these nine judgments are issues involving company law (the interpretation of corporate constitutions), trust law (the admissibility of extrinsic evidence to prove a gift), arbitration (whether parties are bound by the arbitration agreement), credit and security (the construction of performance bond contracts), conflict of laws (the interpretation of a jurisdiction clause), shipping law (the interpretation of bills of lading), and the interpretation of settlement deeds.

Professor Soh’s research further demonstrated how network analysis could shed light into the development and renewal of Singapore law. In particular, it lets us visualise how certain judgments rise to legal prominence, in the process displacing older ones.

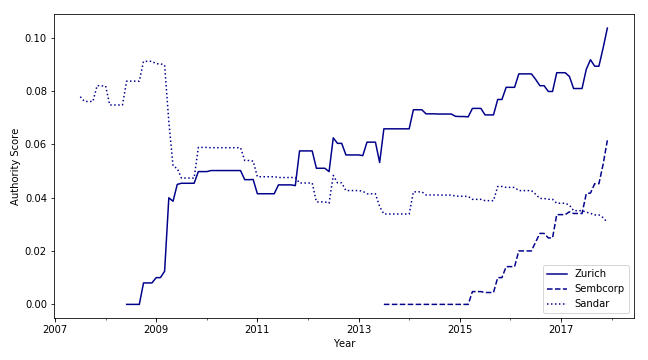

Figure 2: Patterns in authority scores for selected cases

In his paper, Professor Soh relies on a graph of network centrality scores over time to narrate a ‘tale of three cases’ (Figure 2). The story begins with the Sandar Aungjudgment which, decided on March 2007, laid the foundations for a contextual approach to contractual interpretation in Singapore. Sandar’s authority score, however, steadily diminished after Zurich Insurancewas decided in 2008 and the latter’s influence grew.

Meanwhile, although the Sembcorp Marinejudgment that was handed down on July 2013 did not appear to gain momentum immediately, its authority score began to grow exponentially post-2015, after the judgment was reaffirmed by the Court of Appeal in two later cases.

Interestingly, however, Sembcorp Marine'srise did not trigger a fall in Zurich Insurance’s centrality, which continued to grow post-2013. Why was Zurich Insurancenot overtaken by Sembcorp Marine,in the same way that Zurichitself had overtaken Sandar Aung? Professor Soh provides an explanation grounded in both law and economics: while Sandarand Zurichwere substitute citations deciding the same point of law, Zurichand Sembcorpestablished mutually-reinforcing doctrines of law and were better seen as legal complements.

Overall, the study showed that network analysis provides an automated empirical method to identify patterns in legal judgements, such as the dynamics of their evolution in the network and their centrality, without having to manually analyse each case.

Citations and nuances count

Professor Soh next explains that network analysis offers insights that simple citation counts do not because such counts capture less nuanced information.

“Network analysis’s potential lies in the ability to quickly analyse hundreds if not thousands of cases and identify the most interesting legal phenomena and precedential structures,” he observes. “There is no reason why authority scores over time cannot be generated for any other Singapore judgment and compared against others.”

Network analysis could help practitioners select the most central authorities to cite in the course of submissions (particularly to support propositions of law). “If a proposition on contractual interpretation is being made and the submission drafter, working under time and page-length constraints, wants to identify the best authority to cite out of several candidates, then centrality measures can quickly show that Zurichshould be preferred to Sandar.” This would be particularly useful for areas of law that the lawyer is less familiar with, and/or if simple citations counts did not point decisively to a clear leading case. Thus, network centrality scores could help lawyers and law firms reduce research cost and research time.

In conclusion, Professor Soh argues, network analysis is a useful empirical tool for studying the Singapore legal system that can and should be explored in greater detail. Professor Soh is currently working on an extension of this project, where he will be analysing a bigger set of Singapore cases and doing a comparison with cases in other jurisdictions such as the US and EU.

Back to Research@SMU Aug 2020 Issue

See More News

Want to see more of SMU Research?

Sign up for Research@SMU e-newslettter to know more about our research and research-related events!

If you would like to remove yourself from all our mailing list, please visit https://eservices.smu.edu.sg/internet/DNC/Default.aspx