Above: Assistant Professor Lin An-Ping of the SMU School of Accountancy presenting his paper titled ‘Happy Analysts’.

By Sim Shuzhen

SMU Office of Research & Tech Transfer – In 2016, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was tasked by Congress to run a unique experiment. To study the effect of tick size – the minimum incremental price movements of trading instruments such as stocks – on market liquidity, the SEC randomly assigned 2,600 small-capitalisation stocks to either a control group, where the minimum tick size was held at the current US$0.01, or to a treatment group, where the minimum tick size was raised to US$0.05.

For economists and finance scholars, this large-scale randomised controlled experiment – known as the Tick Size Pilot Programme – presents a golden opportunity to explore the causal effects of tick size on market dynamics, said Professor Charles Lee of the Stanford University Graduate School of Business. “You rarely are able to make causal inferences as nicely as in this particular setting,” he explained.

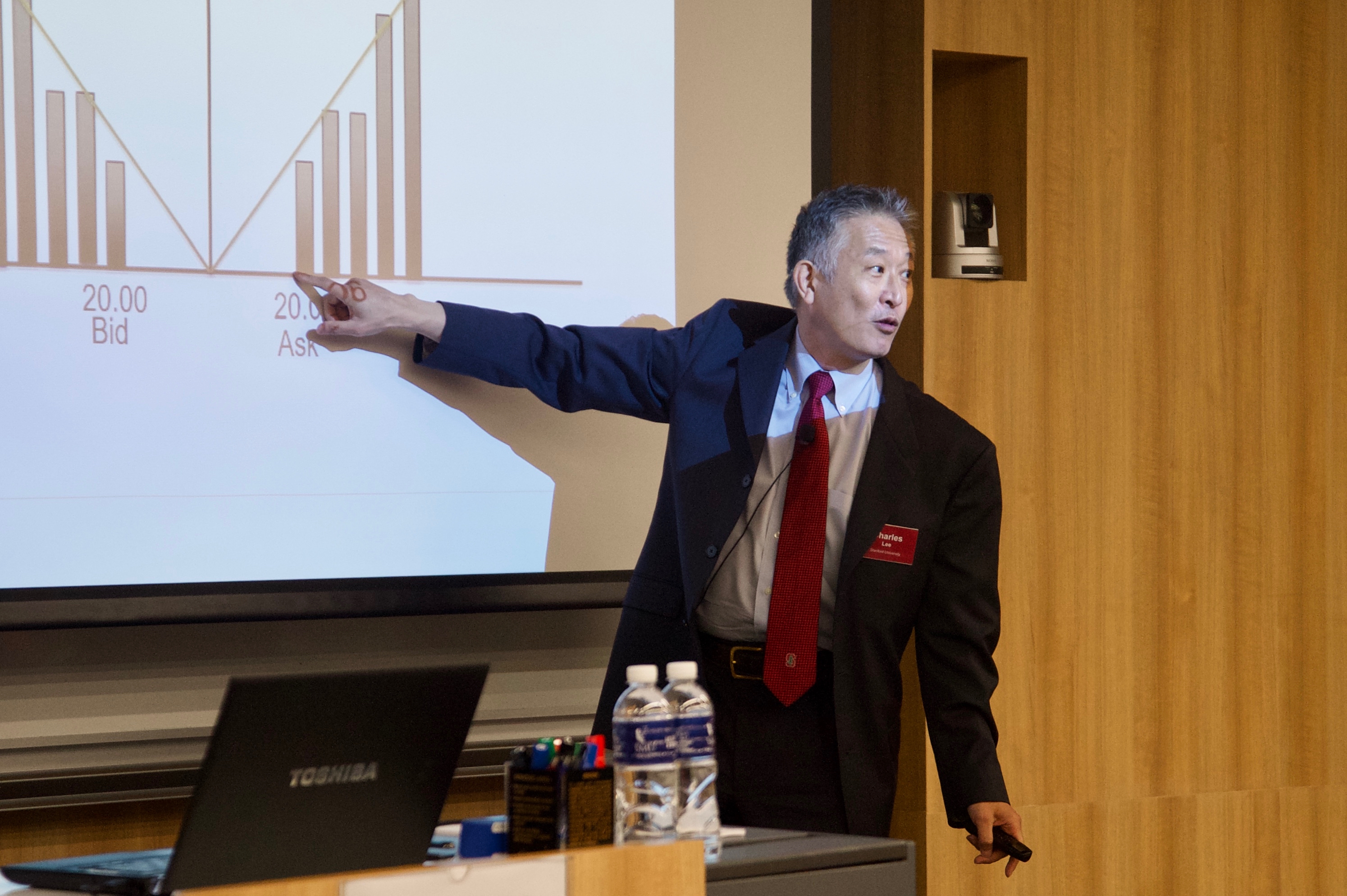

Above: Professor Charles Lee of the Stanford University Graduate School of Business presenting his study.

Using data from the pilot, Professor Lee is studying how tick size affects algorithmic trading – which today accounts for more than 50 percent of trading volume in US markets – as well as market quality. He presented the study, titled ‘Tick Size Tolls: Can a Trading Slowdown Improve Earnings News Discovery?’, during his keynote address at the Singapore Management University (SMU) School of Accountancy Research (SOAR) Symposium, held from 12-13 December 2018.

Above: Professor Cheng Qiang, Dean of the SMU School of Accountancy, giving the opening address at the SOAR Symposium.

First held in 2010, the SOAR Symposium is a key platform for SMU researchers to present and gain feedback on their research, said Professor Cheng Qiang, Dean of the SMU School of Accountancy. “As a young school, it is very important for us to promote ourselves… we also want to give our faculty members, especially junior faculty members, the opportunity to interact with wonderful scholars,” he said.

Tick size, algorithms and information

Despite the high volume of algorithmic trading in today’s markets, how this type of high-frequency, computer-assisted trading impacts market quality – in terms of liquidity and price efficiency, for example – remains an open question, said Professor Lee.

For instance, while algorithmic traders increase trading volume, they could also reduce market liquidity due to their ability to anticipate the direction in which the prices of large trading orders will move. “The nice way of saying it is that they are avoiding information asymmetry risk… the not-so-nice interpretation is that they are preying on larger and slower orders,” explained Professor Lee.

By analysing data from the Tick Size Pilot Programme, Professor Lee and his co-author Mr Edward Watts found that increased tick size results in a sharp decline in algorithmic trading activity. “It’s like putting speed bumps [in the algorithmic traders’ way]… [previously], they could improve the price by one penny and jump ahead of the entire wait queue. We think that if you put in these five-cent increments as speed bumps, their activity will drop, and we do see that,” he explained.

This decline in algorithmic trading was accompanied by a sharp drop in price volatility and trading volume around firms’ earnings announcements, indicating a muted market response to earnings information, said Professor Lee. In addition, investors were more active at acquiring fundamental information about firms in the treatment group, such that these firms’ pre-earnings announcement prices better reflected future earnings announcements.

Overall, the study shows that an increase in tick size can lead to better price informativeness, although it remains unclear whether or not the observed decline in algorithmic trading is driving this, said Professor Lee. “We do not provide causal evidence that it is the decrease in algorithmic trading that increases fundamental information acquisition. It is conceptually sensible and we have no other mechanism, but we didn’t manipulate algorithmic trading, so we have to be careful.”

Work-life balance – more isn’t always better

Unlike algorithmic traders, which do not need to eat, sleep or spend time with their families, work-life balance has become an increasingly important concern for human financial analysts who work notoriously long hours, said Assistant Professor Lin An-Ping of the SMU School of Accountancy, who presented a paper titled ‘Happy Analysts’.

While many investment banks and brokers have started to implement work-life balance policies such as reduced working hours and paid sabbaticals, the impact of these policies on analysts’ careers remains unclear, said Professor Lin. “Financial analysts’ actual workload has not changed – if they don’t work now, they still need to find some other time to do the work,” he explained. “Their work is also very time-sensitive – because of the information demand from clients, they may not be able to take a break.”

By analysing a large sample of nearly 12,000 Glassdoor employer reviews submitted by analysts, Professor Lin and his co-authors found that when analysts’ satisfaction with work-life balance was low, improvements to work-life balance were associated with better performance and career advancement. “The effect can be positive if better work-life balance is associated with lower job stress and better mood, as this can facilitate analysts’ social interactions with their connections… lower job stress and better mood can also have a direct impact on performance, because these analysts are healthier and more productive,” explained Professor Lin.

However, if work-life balance satisfaction was already high, further improvements to work-life balance were actually detrimental, the researchers found. “If better work-life balance results from less work involvement, this can mean less social interactions with clients and other connections, which can eventually hurt performance and career outcomes,” said Professor Lin.

This non-linear relationship suggests that there is an optimal level of work-life balance, and has implications for both employees and employers, said Professor Lin. “We hope our findings can add to the debate on the importance of work-life balance in the financial industry – many brokers are trying to improve work-life balance, but they also need to think about the potential effect on employees’ performance and careers,” he concluded.

Back to Research@SMU February 2019 Issue

See More News

Want to see more of SMU Research?

Sign up for Research@SMU e-newslettter to know more about our research and research-related events!

If you would like to remove yourself from all our mailing list, please visit https://eservices.smu.edu.sg/internet/DNC/Default.aspx